by Patrick W. Carey.

Wm. B. Eerdmans (Grand Rapids, Mich.), 2004.

448 pp., $29.00 paper.

Alexis de Tocqueville, in Democracy in America, predicted that Americans “will tend increasingly to fall into one or the other of two categories: those who abandon Christianity entirely, and those who join the Roman Church.” In the rapidly democratizing United States of the 1830s that historians refer to as Jacksonian America, individualistic Americans, Tocqueville noted, seemed “inclined to shun all religious authority” in their search for equality and “a single social power that is both simple and the same for all.” Yet he rested his prediction on the conviction that there existed “a hidden instinct that propels them unwittingly toward Catholicism.” Even if practical and restless Americans at first glance might find themselves astonished by Catholic doctrines, they could not but admire the Church’s “great unity” and the efficiency with which it was governed. This was Catholicism’s strength, and the basis for Tocqueville’s assertion that the “Roman Church” was more suited to the American mind of what he called the “democratic age” than to a European mind still wedded to the union of throne and altar that belonged to the fast-fading “aristocratic age.”

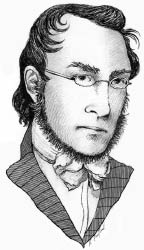

Brownson’s contemporaries found his religious path inexplicable, leading one to label him a “Religious Weathervane,” a sobriquet which serves as the subtitle of a new biography of Brownson by Patrick W. Carey. Carey is professor of theology at Marquette University and editor of The Early Works of Orestes A. Brownson (currently at six volumes). He also has written several monographs and articles on the core of much of Brownson’s writings, namely, the interplay between Roman Catholicism and American republican principles.

Orestes Brownson had the unenviable circumstance to work out in public what most people engage in privately: his journey in and toward faith. Carey traces the principles that consistently formed the outer boundaries of Brownson’s journey throughout his life. He sets this tale in the cultural milieu of the 19th century Atlantic world. Carey, however, argues that despite his religious and philosophical transformations, Brownson’s life’s work nevertheless forms a coherent search to harmonize freedom and communion in a way that equally applies to one’s relationship to God, to nature, and to society. “His passion,” argues Carey, “was for logical consistency.”

Carey’s Brownson is a man of the world, not simply of New England or of the United States. This is the book’s great strength, for in a larger sense Orestes A. Brownson also is a survey of 19th century philosophy. Indeed, anyone seeking to understand the interplay among mid-19th century intellectual trends, philosophy, and Catholic theology will find in Carey’s book a series of succinct explications of topics ranging from neo-Thomism and the Syllabus of Errors to the mid-19th century debate over papal infallibility and the American tendency toward Pelagianism.

Brownson’s philosophy evolved significantly not only just after his ineffable moment in 1842 just prior to his Catholic conversion, but also when he encountered for the first time thinkers such as Pierre Leroux, Victor Cousin, and Immanuel Kant. The tone of Brownson’s writings also varied according to what he perceived to be the present needs of society, and each time he made new enemies. For example, Brownson was criticized as ultramontane, anti-liberal, and slavish because of his approval of Pius IX’s Syllabus of Errors (1864). Brownson argued that the Syllabus condemned only the secular “spirit” behind modern liberalism, not its forms. True, he admitted, Pius IX’s language sounded harsh to American ears, but Rome based its stance toward liberalism and the disestablishment of state churches on its experience with the bloody French Revolution and the upheavals of 1848, not on American republican practice. In the wake of the Syllabus, Brownson took unto himself the task of explaining how Catholic dogma and republican principles complemented, rather than contradicted, each other.

“Error has no rights,” Brownson once said, “but the man who errs has equal rights with him who errs not.” This summation of how Catholics ought to view religious freedom this time led some of Brownson’s co-religionists to accuse him of liberality and modernism. But like Isaac Hecker, his friend and contemporary, Brownson “saw Catholicism as the happy medium between the two American extremes” of Calvinism and Transcendentalism. Calvinists sought to use the state for religious or humanitarian ends, making truth, in effect, the result of crass majority rule. Transcendentalists rejected tradition and authority in the name of the individual. Thus, each ignored critical truths about human nature and the proper relationship of man to the state. Brownson was convinced that Americans would find the Catholic Church the highest expression of community only if Catholic dogma could be presented clearly to them in a society free of demagoguery and coercion.

Brownson’s search for logical consistency and balance ultimately led him to challenge “popular notions about the relationship between religion and the state.” Brownson condemned those who divorced “the spiritual and political orders” in their attempt to prevent the formation of a centralized, ecclesiastical state. The First Amendment, admitted Brownson, forbids the union of “religious and political institutions.” But this does not mean that politics ought to be or even can be “a completely autonomous sphere of existence untouched by moral or religious considerations,” for the Church possesses a unique voice in all matters affecting “moral and religious issues and ends.” This opinion placed Brownson at odds with many Catholic politicians, who, in the face of widespread anti-Catholic sentiment, defended their loyalty to the United States by supporting a complete separation of a religiously-grounded ethics from policy questions. Brownson thus labeled his Catholic critics demagogic “political atheists,” who, he said, eventually would find themselves acting contrary to truth and their professed faith just to win elective office.

Carey’s Orestes Brownson is an excellent and much-needed addition to the literature on Brownson. It is a comprehensive study of Brownson’s intellectual growth explained in light of his philosophical mentors and set against the background of American and European politics during the 19th century. Once Catholic, Brownson spent the rest of his life exploring, polemically at times, the relationship Catholicism has or ought to have to republican government and, more specifically, to the American experiment. Because of his views on the interplay between religion and the state, Brownson may well be more important in the 21st century than he was in the 19th, since the fight over this relationship continues unabated and even grows. Orestes Brownson, then, is also a timely rumination on today’s culture wars, accomplished through the biography of a man whom Russell Kirk declared “one of the most interesting of all Americans” who “defended the permanent things.”

John C. Pinheiro is assistant professor of history and Director of Catholic Studies at Aquinas College in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Co-editor of Volume 12 of the Presidential Series of the Papers of George Washington, he is the author of Manifest Ambition: James K. Polk and Civil-Military Relations during the Mexican War (Praeger, 2007).