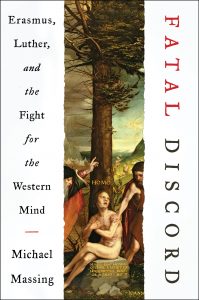

by Michael Massing.

HarperCollins, 2018.

Hardcover, 987 pages, $45.

Daniel James Sundahl

Michael Massing’s thesis in this massive undertaking, Fatal Discord, argues that the rift between Erasmus and Luther—now some five hundred years past—defines the rippling course then taken by the Western mind. It’s an engrossing dual biography suggesting the disputes between the two men gave rise to colliding traditions with us to this day. Both were developing new designs for living by rebelling against the restraints of the Roman Church. For Massing, Erasmus and Luther’s historical time is the fault line “when the medieval gave way to the modern.” The two enduring forms of thought illustrate the beginnings of Christian humanism and evangelical Christianity.

The “how” is devoted to the way we read the Bible—and which translation—which is not to do an injustice to Massing’s thesis but to illustrate the disparities or entanglements between two forms of thought.

In his books and essays, Erasmus laid out a program of reform hoping to “enlighten” European intellectual and religious life. His fundamental argument? Religion should be “more about conduct than doctrine.” To accomplish this reform required a revolutionary new way to read the Bible which would form the humanistic view that man is a fully autonomous moral agent.

For Luther extolling human dignity placed too much stress on the capabilities of man. His manner of reading the Bible began with a revolutionary reading of Paul’s epistles—the letter to the Romans especially—and what becomes the “core” of evangelical Protestantism: the doctrine of justification by faith alone, which implies the utter worthlessness of man before God.

For Massing, the competition between these counterpoints flared into bitter competition, each attempting “to win over Europe to his side.” The general starting point for Erasmus was the Vulgate of Jerome, that late-fourth-century Latin translation that was affirmed as the Catholic Church’s officially promulgated version at the Council of Trent. Massing’s scholarship is pointed; he’s concerned with the manner in which Erasmus does not simply embark on a new version but traces the nature of Jerome’s earlier work found in his correspondence. Erasmus’s own translation, then, is dependent not only on the accuracy of Jerome’s translation of the New Testament Greek into Latin but the Old Testament’s Hebrew into Latin. The result is an “Old Latin Bible,” which for Erasmus meant not uniformly edited or translated or improperly redacted by later unknown revisers.

Such might seem “miniscule” these days, but Erasmus was unyielding on the subject of Scripture—more so with the likelihood that some “drowsy scribe had [once] corrupted something or that some unknown translator had made a poor rendering.” All of which might pass our attention unless we understand Erasmus’s scholarly apparatus, which underlies his Christian humanism. Massey is at pains here to illustrate how Erasmus is intent on going back to the original sources of the Christian faith as an antidote to the corruption in the church of his own day. His Greek New Testament, usually cited as the first “critical edition,” drew from all available manuscripts to compile a text with wording as close as possible to that of the original “inspired” authors, and to correct the Latin copies by going back to the Greek.

That “critical edition,” when printed, was to appear in parallel columns, Erasmus’s Greek edition in one column and his “New Latin” text as the other column, both aided by Erasmus’s annotations. His New Latin text is thus an “uncovering” of words from the Greek that had become over time corruptions in the Vulgate. With his scholarly Latin and Greek, Erasmus thus presumed he had found a way “to better capture the plain, colloquial way in which he believed the apostles spoke … [their] popular speech.”

Why spend time on this?

Massing cites good examples of Erasmus’s then-controversial handling of New Testament passages, noting that “… at many key points, he ventured beyond the philological, using grammar to challenge interpretations that had reigned for centuries and hardened into dogma.” It’s a delicate problem in as much as his New Latin text questions whether marriage is a sacrament and whether penance means to wash away one’s sins with some prescribed penalty (which had become a powerful weapon in the clergy’s arsenal) or whether the Greek metanoia more likely means to come to one’s senses afterwards—in effect, recognizing one’s error.

It’s not an understated point—Erasmus’s New Testament became a milestone in biblical scholarship—but he also advanced his “philosophy of Christ,” which is a piety modeled on the life of Christ, simpler and more intense than some medieval versions. Salvation is thus based on deeds of love, Christian ethics, and humanist principles.

What would be the consequences for the Western mind? It is far from being radical, but that we are made in the image of God is the basis of individual worth and human dignity and social justice. Salvation is still the consequence of faith in God, but also faith in the capabilities of man to travel up and down that moral scale understood as the produce of free will. Massing concludes that by studying Erasmus’s life one can “unlock the origins of modern-day humanism both in America and in Europe.”

Martin Luther, whose biography “duels” with that of Erasmus, is grounded in the “Ninety-five Theses,” his proposition for a debate over the question of indulgences. The issue? The doctrine was uncertain in the Roman Catholic Church prior to the Council of Trent, which defined the doctrine and eliminated abuses. Prior to the Council, “indulgences” were commutations for money, a penalty due for sin, but also regarded as part of the sacrament of penance. Abuses became common.

Massing is clear on this issue, noting that Luther, a stout German and professor of moral theology at Wittenberg, was one with the German people in resenting the money they were forced to contribute to Rome.

His argument? Indulgences are not evidence of true repentance but more likely attempts to avoid repentance and sorrow for sin. One’s entry into Paradise cannot be had by a handful of indulgence certificates. Equally to the point is Luther’s argument for the bondage of the will, that protesting shot heard around the world and a rebuttal of Erasmus’s argument for a free will.

For these “reformers” it was no mere academic question. For Luther such was the cornerstone of the gospel and the biblical doctrine of grace: without God’s grace the will is not free at all but a permanent bondslave of sin. For Erasmus, in contrast, Christianity was essentially morality and the will was free, and in this context gave a power to mankind by which one could apply oneself to those things that lead to eternal salvation; in other words, the will does not need grace to have effective power.

The two men never met but carried on a correspondence, often vitriolic from Luther’s pen, and thus became implacable foes. Their collision is with us today, culturally and even politically. Reading Massing’s sprawling treatise forces the reader to look into the spirit of one’s own belief: human perfectibility or the incorrigible depravity of human nature?

Into that narrow space is a consistent argument challenging authority, church, and state. But also in that narrow space is the violence of certitude, that “fatal discord” leading to “rupture.” And although sprawling, Massing’s narrative is compelling. Part VI, “Rupture,” is a poignant telling of the “Peasants War,” an effect of the erosion of the authority of the Vulgate, but also an effect of various radical preachers. It is a fateful moment of turmoil in Germany and France. For sheer butchery on May 17, 1525, Alsace stands out. Peasant defenders took refuge in a church but were burned out. Begging for mercy when rushing from the building “they were mercilessly cut down. In all, between two thousand and six thousand were slain. The East European mercenaries added an element of cold-blooded cruelty. Children as young as eight, ten, and twelve were killed; women and girls were dragged through the cornfields, raped, and murdered.”

Such events are tragedies, of course, erupting from theological splintering and surely regrettable. One can, however, debate whether Massing is correct in arguing whether Erasmus’s and Luther’s influences are still with us. His suggestion that much of modern philosophy is born from Erasmus should suffer from some skepticism. There may be birthright influences, but such a tracing would fast become encyclopedic.

American evangelical movements, on the other hand, are more evident and Massing is on point in arguing that America’s Great Awakenings owe as much to Luther’s creed as to John Calvin’s. Massing cites the late Billy Graham as being on record as to Luther’s influence on his ministry. One may disagree but it’s likely true that the Reformation seems to have forged America more than the Renaissance.

As for Europe, there’s a pointed reminder from World War II; according to Massing the rise of the European Union owns an accord with Erasmus’s cultural programs for unity within diversity. But equally so is the reminder of Bonhoeffer’s life and the Confessing Church’s opposition to Hitler. If all Christians are priests, as Luther argued, there is a cost to that discipleship and evidence of that fatal discord.

Daniel James Sundahl is Emeritus Professor in English and American Studies at Hillsdale College where he taught for thirty-three years.